The Invention of Truth

How Law, Language, and Power Conspired to Define What’s “Real”

It started with a comment on LinkedIn.

I had just posted a link to my previous piece on the storytelling power of fiction, and someone replied:

“A little contradictory, but isn’t ‘made up’ the definition of fiction?”

Fair point. My answer was blunt:

“In the extreme, we make all memories up. Nothing is ‘true.’ Truth is actually a convention that largely came out of the foundation of a legal system way back when.”

It wasn’t meant as a philosophical grenade, but maybe it landed that way. Because the more I thought about it, the more it begged to be unpacked.

If truth is made—manufactured, agreed upon, encoded—then who made it?

And why does that matter for how we live, argue, remember, and believe today?

French philosopher Michel Foucault wrestled with exactly this question.

He proposed something radically simple:

What we call “truth” in the modern world is not an eternal ideal.

It’s a product of power, rooted in the invention of law itself.

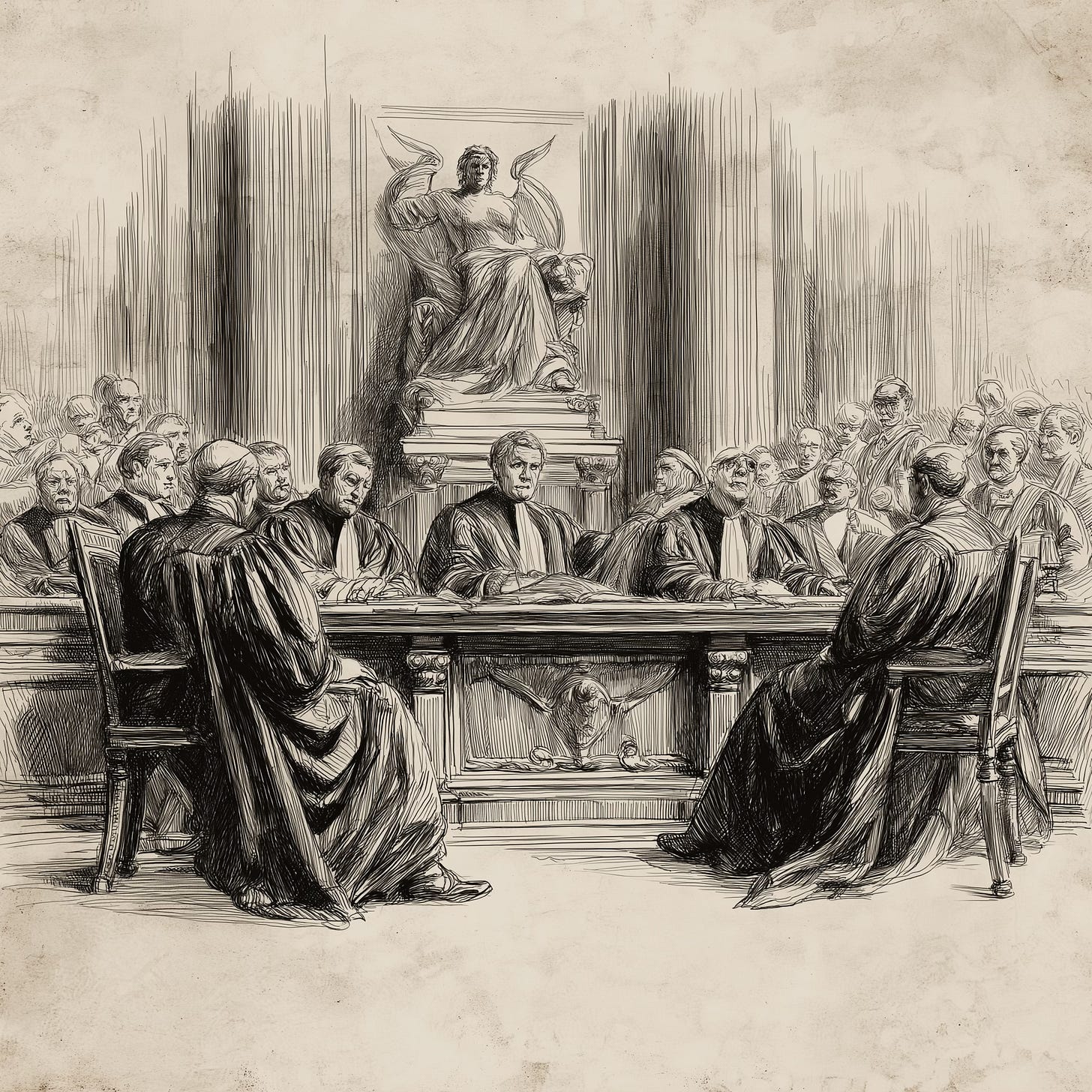

Truth on Trial: From Gods to Judges

Foucault’s argument isn’t that truth is fake—it’s that it’s constructed.

Specifically, that the modern idea of truth as something verifiable and reasoned comes not from science or religion, but from legal systems and the procedures they invented for settling disputes.

He starts with Homer. In The Iliad, truth is divine. You swear an oath to the gods, and your honesty is judged by fate or favor. Justice is sacred, ritualized, and tied to the heavens.

But by the time we get to Oedipus Rex, the gods are no longer the final arbiters.

The play’s power comes from inquiry—witnesses, clues, prophecies, and pieced-together fragments.

This, Foucault says, is the prototype of the legal model of truth.

Fast-forward to medieval Europe. Courtrooms take center stage.

Truth becomes something produced—not by divine revelation or brute strength—but by procedure:

sworn testimony,

evidence,

argument,

and the authority of the record.

No more trial by fire. No more duels to settle disputes.

Now, it’s trial by language.

And this legal machinery—designed for taxation, property claims, or criminal judgment—lays the foundation for how we still think about truth today:

Something you can prove.

Something you argue.

Something that exists inside a system.

The Exam Room Replaces the Battlefield

As law evolved, it exported its methods elsewhere.

First to administration. Then to education, medicine, psychiatry—and eventually, science.

Foucault’s concept of power-knowledge explains how institutions generate truth:

They observe.

They classify.

They document.

And by doing so, they make something real.

When you’re diagnosed by a doctor, labeled by a test score, or evaluated in a job review, you’re not discovering truth.

You’re entering a system that produces truth—truth about you.

These mechanisms didn’t descend from heaven. They descend from courtrooms.

And like the law, they are:

abstract,

procedural,

and mediated by language.

Even in science, what’s accepted as “true” often emerges from peer review, replication, and consensus—a kind of intellectual trial, conducted by experts, written in code, and archived in journals.

Foucault borrows from Nietzsche here:

The will to truth is born not of dispassionate inquiry, but of older instincts—instincts for order, for control, for rule.

What was once force is now form.

Or as Foucault famously put it:

“Truth is a thing of this world.”

Beyond the Verdict: What Else Could Truth Be?

Of course, not everyone buys this.

Philosophers like Aristotle grounded truth in correspondence—saying what is is, and what is not is not.

This view sees truth as alignment with reality, independent of procedure.

Others argue for coherence (truth is what fits together), or pragmatism (truth is what works), or metaphysics (truth is what is, regardless of what we say).

Even within law, there’s a distinction between legal truth (what the system accepts) and factual truth (what actually happened).

Sometimes those align.

Sometimes they don’t.

Still, Foucault’s view has bite.

Especially now.

Because in the 21st century, truth increasingly looks like litigation.

Arguments are staged like court cases.

Receipts and evidence flood timelines.

Trials happen not in court, but on YouTube, on X, in the court of public opinion.

We don’t just search for truth—we prosecute it.

So when I said truth is a legal invention, I wasn’t dismissing reality.

I was asking us to consider how deeply language and systems shape what we accept as real.

If truth is something we built, then maybe we can also rebuild it.

And if storytelling is how we began to make sense of ourselves before the law ever existed, then maybe we ought to revisit how stories—and not just procedures—can lead us back to something real.

Something truer than truth.